- BIENVENUE

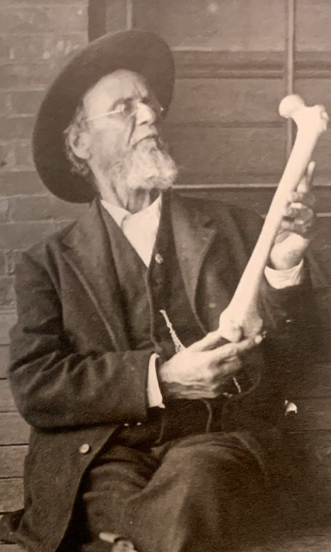

- AT STILL De l'os sec à l'homme vivant par John Lewis DO

- LE PROJET BONE ( en français )

- THE BONE PROJECT (in english)

- DAS BONE-PROJEKT ( In Deutsch)

- Bonnie Gintis D.O

- Dr Steve Paulus D.O 11-13 octobre 2021

- AGENDA

- SOCIETES AMIES

- EurOCA

- PAROLES D'OSTEOPATHES

- CONFERENCES

- C.O.R.P.U.S

- Introduction à une phénoménologie de la perception ostéopathique

- Embodied Mind Project 2013

- Cambridge CEP 2014 Conference

- Conférence SFDO 2014

- Lectures croisées des théories et des pratiques du corps – Orient et Occident

- Ecole Française de Daseinanalyse

- Les frontières du vivant et du non-vivant et l’unité de la nature.

- EHESS : L'odyssée d'un ostéopathe en quête de la Santé

- JOURNEES RESONANCES

- DOCUMENTS

- OIDA

- PRIX de la SOFA

- SOFACULTY

- ESPACE MEMBRES

- PETITES ANNONCES

- CONTACTS-INFO

- VIDEOS COURS SOFA

- 1874-2024 L'ostéopathie a 150 ans

EDITORIAL:

Since 2008, French osteopathy has been officially regulated and its training supervised by rigorous but uninnovative academic programs resulting more from a political and socio-professional balance than from a genuine scientific, phenomenological, and clinical impetus serving the osteopathic profession and its patients.

As a result, there is a profound gap between the reality of osteopathic practice among practitioners who have integrated, among other things, tissue models or the biodynamic model of osteopathy, and the classic musculoskeletal biomechanical osteopathic model that serves as the legal reference for manual medicine.

This difficulty stems primarily from the confusion between models that respond to different goals and registers of knowledge, as brilliantly analyzed by the philosopher of science Bruno Latour. The biodynamic model of osteopathy, for example, as developed by Dr. Jealous from 1993 onwards, is essentially a phenomenological model for teaching the perception of fluids and not a scientific model in the strict sense. It therefore does not claim to represent an academic scientific view that can be reduced to the data acquired by science. Its purpose is rather to support osteopaths in their perceptual development by providing them with a phenomenological roadmap informed by the achievements of the osteopathic tradition. Historically, clinical osteopathic practice has always preceded attempts at scientific explanation. Few osteopaths have found their vocation by reading scientific articles!

Thus, the classic biomechanical and neurological scientific model, which still largely dominates general osteopathic teaching in schools and research, struggles to account for the richness and complexity of clinical practice as it is experienced on a daily basis in osteopathic practices.

Two dangers currently threaten osteopathy.

On the one hand, the dumbing down of teaching through conformism and the desire for recognition. The current transformation of British osteopathic teaching, with its slow drift towards assimilation into physiotherapy and the collapse in student numbers at the BSO and the European School of Osteopathy in Maidstone, should alert us to this. Brexit is only partly to blame for this!

On the other hand, there is our difficulty in embracing the originality of osteopathic medicine and developing research programs that correspond to the real needs of the profession, rather than focusing solely on subjecting it to inappropriate validation criteria.

In doing so, the political injunction to bring the practice of osteopathy into line with what appears to be scientifically acceptable is a weapon that is now being used successfully by the socio-professional opponents of osteopathy.

To respond to this challenge, it became clear to us that SOFA could usefully contribute to the formulation of a new scientific model of osteopathy, expanded to include the most recent scientific data (Jo Buekens' course is a striking example of this, as his vision of bone is based on the most recent scientific data while remaining rooted in osteopathic philosophy and serving patients). The purpose of this model will be to communicate better with the medical and scientific world, not to replace the traditional phenomenological teaching models that are our most precious heritage and the source of our professional identity, but which respond to a different register of knowledge.

The current challenge for osteopaths is therefore to articulate a renewed scientific model of osteopathy with the phenomenological models of traditional osteopathic teaching, but not to unify them.

Thus, the philosopher of science Bruno Latour invites us not to confuse chains of reference with chains of transformation: a scientific model derives its validity from the solidity of the inscriptions (measurements: graphs, images, figures, formulas, etc.) that link the measured phenomena to their representations, while a phenomenological map derives its validity from its power to modify the attention and practice of osteopaths. Confusing these two regimes is like changing the rules of the game in the middle of the game (see the following article entitled Bruno Latour's warning).

It was to contribute to this necessary aggiornamento of the academic osteopathic model that the BONE PROJECT was launched two years ago.

Its ambition: to explore the most recent scientific and clinical data in order to profoundly renew our understanding of osteopathy and clarify the communication of osteopaths with their patients and the academic world.

In order to initiate this renewal of the classical osteopathic model, it seemed to us that the best starting point for an osteopath was to return to the founding intuitions of AT STILL and thus rediscover his vision... of the living bone. Too often reduced to a simple biomechanical structure, bone is in fact much more: a living, dynamic organ at the heart of the body's physiological and fluidic balances. So, to paraphrase our friend John Lewis, who titled his beautiful biography of A.T. Still “From Dry Bone to Living Man,” we aim to revitalize the osteopathic model by starting with living bone and moving toward a more dynamic and original model of osteopathy.

That is why we have chosen to launch PROJECT BONE with a founding event: a course by Jo Bueckens entitled The Secret Potential of Bone in Osteopathy. Over the past two years, we have had the opportunity to meet Jo, exchange ideas with him, and discover his innovative work that reinvents bone, no longer as a simple mechanical framework, but as an organ in its own right—notably a vascular, erythropoietic organ at the heart of circulation and vital regulation.

His perspective and highly accomplished clinical practice renew and extend Still's great rule of “arterial supremacy” , and re-establish osteopathy in the legacy of the pioneers, notably that of Professor Michael Lane, a major figure in osteopathic physiology at the beginning of the 20th century, who, as early as 1916, presented osteopathy as a medicine of the immune system.

JO is the author of a remarkable book, BONE THE BEST-KEPT SECRET, which has not yet been translated into French and is only available on Jo Buekens' website.

This inaugural course will take place in November, in Dijon from November 6 to 9, 2025, at the Hôtel du Parc, and will mark the official launch of the BONES project, which will span several years. This project is expected to run until 2028, with the organization of intermediate symposiums and a final conference in 2028 dedicated to bone in osteopathy and the 20th anniversary of SOFA, whose ambition will be to present the results of the research carried out over the next four years and thus contribute effectively to the emergence of a new general scientific model of osteopathy.